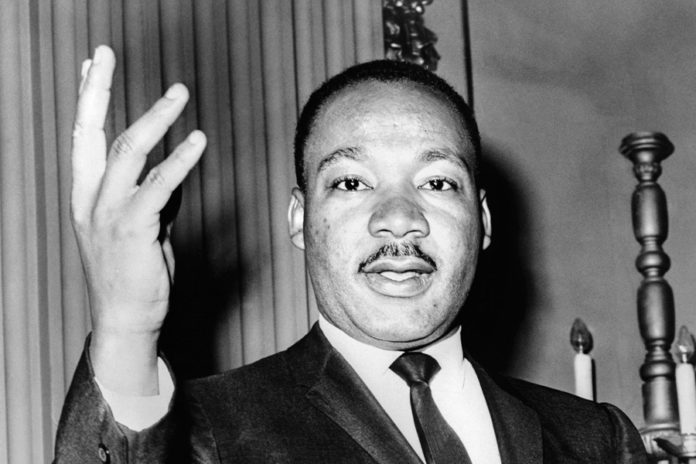

In College in the early 60’s I began to learn about Luther King, Malcolm X, and many others in the Black Civil Rights Movement. I was a Junior at the University of Colorado Boulder when King was killed on April 4th, 1968. King was my hero and I loved him and his work. He was a man who preached nonviolence and sacrificed so that all might have their civil rights respected. At that time in 1968, there were about 40 blacks on Campus, mostly athletes, and 11 Latinos.

Youngsters from the SDS, the Students for a Democratic Society, soon were at my door hours after King’s death, asking me to join them and Black Athletes the next day, to talk about King and racism in America. I had never spoken at a demonstration and was most hesitant. But this SDS organizer convinced me that I should talk about my experience with racism in Colorado. And I asked if this could wait for three years, as by then I would have graduated from Law School and would know what to say.

While I was in tears and devastated by his murder, I was also nervous about becoming a demonstrator; but my hesitation did not deter this SDS leader.

He said: “History cannot wait!”

“what do you mean History can’t wait?” I demanded

“King died today, and you must speak tomorrow”, he insisted.

Well, the white activists, the black athletes and I spent the rest of the semester demonstrating; demanding, and obtaining programs for black students that made it possible for them to play Quarterback for the University Buffaloes; and also, be able to date anyone they might want. In addition, we got rid of the admission exams, which were hindering the entrance of people of color.

When you stand up for human rights, those who oppose you suddenly come out of the woodwork. I was on occasion chased through the campus by white racist students who wanted to beat me up. When not chasing me, they would call me racist names. And there was no Raza (my Chicano people) there to defend me. Luckily, I was thin and could run fast; but they never chased nor harassed me when I was with the Black athletes.

Later on, other students who came to the University as a result of our demonstrations took credit for our efforts.

Disappointed in the response by so many white students I left the university for 5 years, to do farmworker organizing with the United Farmworkers, found my Chicano roots, became an anti-war activist, and soon, a candidate for La Raza Unida.

By 1985 I was in Atlanta, working for Amnesty International with King’s widow Coretta Scott King, Rev. Joseph Lowery the President of SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference), and, in the process, got to work with other civil rights figures like Rosa-Parks, Fred Shuttlesworth, Dick Gregory and Congressman John Conyers of Detroit, who first introduced the MLK Holiday bill four days after King’s assassination.

Conyers continued to introduce the holiday bill every year until it passed and was signed by President Ronald Reagan on Nov. 2nd, 1983. In January on King’s birthday in that year 1983, we attended the last demonstration demanding his birthday memory on a snowy day in Washington D.C. This event was sponsored by Rep. John Conyers and the Choir Director that day was none other than Stevie Wonder, who sang his classic version of Happy Birthday. And months later we saw Reagan sign the bill for MLK’s holiday.

This was a good reminder for us that when we know something is right and necessary, that we need to work hard and for a long time to obtain it, no matter the adversity and the obstacles. All movements for human rights must be part of our agenda and be included in our vision of freedom.

And my work for the rights of Blacks was most important in the development of my life’s work and my understanding of the inclusion of everyone. When we stand up for the rights of others, we, in fact, are ensuring that our own rights will also be protected.