Last week, the advocacy group LatinoLines announced its response to the new district maps proposed by the Pennsylvania state legislature. LatinoLines was created in 2010 by several Latino non-profits to provide input to the redistricting process, with a focus on the growth and movement of the Latino community, and to help ensure Latinos have appropriate levels of representation in voting districts. This week, Miguel Concepción, a member of the leadership of the LatinoLines coalition, spoke with Impacto newspaper to give a bit more detailed insight into the group’s advocacy process and areas of focus for this year.

Mr. Concepción explained that prior to the release of the state’s proposed maps, LatinoLines had prepared their own versions of the maps, as several other advocacy groups also did (in Pennsylvania and across the country). These versions were prepared so the Latino community would be ready to immediately present its opposition if the state’s proposed maps contained any violations of the legal requirements for voting districts. LatinoLines was involved in the fight to undo the gerrymandering following the 2010 Census and redistricting process, when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ultimately ruled the maps illegal and required new ones be drawn. This time around, however, according to LatinoLines and other analysts (including the Latino Justice legal team), the state’s proposals seem to meet the minimum legal requirements in terms of being compact, contiguous, and preserving political subdivisions. Therefore, LatinoLines versions will not be released; instead, LatinoLines leadership will encourage Latino communities to look more closely at the maps that have been drawn, to understand the details below the surface.

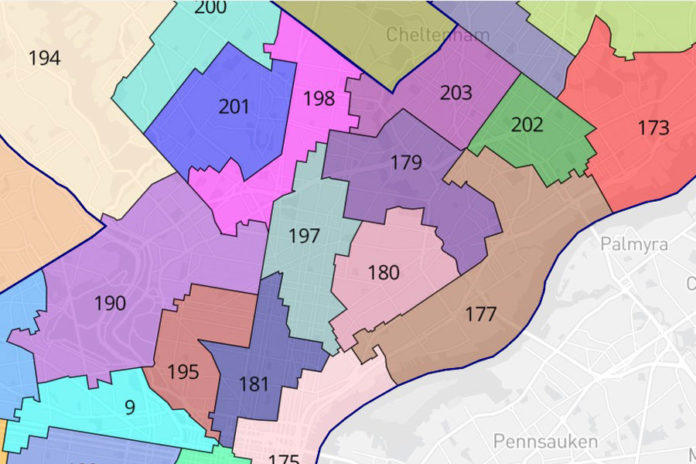

First, Miguel states, it is important for voters to remember that the total number of Latino residents in a given district does not provide a clear picture of their power at the polls. Latino communities are, on average, younger than other demographic groups; have higher percentages of incarceration; and have higher percentages of immigrants. All these factors impact eligibility to vote, and both groups are included when the state is drawing the lines. Therefore, while a district may contain many Latinos within its boundaries, a lower percentage of those are likely to be eligible to vote than districts with different ethnic compositions. According to data from the 2016 election, 71.5% of all Americans are eligible to vote. In the proposed versions of the Latino-dominant state House of Representative districts 179 and 180, 41% and 57% of the districts’ populations are Latino (respectively); but only 68% of the Latinos in those districts are even of voting age – already less than the national percentage, without accounting for other factors such as incarceration or citizenship. At the local level, where smaller numbers of votes decide an election, a few percentage points can make a big difference. Thus, it becomes even more important to keep Latinos grouped together within district boundaries, so they can choose their own representation.

Miguel also points out the state House of Representative districts 179, 180, and 197 (all with high concentrations of Latino residents) would also undergo shifts relative to the proportion of Latinos of voting age in each district, from 2010 maps to the current proposed versions. In the state’s plan, the new 179th district would increase the Latino voting age population from 31.7% of the total voters in the district, to 38.9%. The new 197th district would increase the Latino voting age population from 53.5% of the total to 59%. And the 180th district would decrease the Latino voting age population from 65.21% of the total to 54.2%. In this scenario, no district has as strong a position as the 180th had previously. Therefore, although the new maps may appear to give two of the three districts an improvement in their positions, the Latino community’s voting power is also being diluted by becoming more spread out across districts.

The final consideration Mr. Concepción mentions, is that Latinos historically have lower rates of voter registration and turnout than other groups. Consequently, spreading Latinos more “evenly” across more districts may result in harm to all three, when the combination of factors – age, citizenship, criminal history, voter registration and turnout trends – lead to lower representation across the board.

When asked about LatinoLines’ recommendation considering these considerations, Mr. Concepción spoke of the need for Latino community nonprofit and advocacy organizations to collectively create a 10-year plan for engaging the community to address representation issues. He stated that after the 2010 Census and redistricting process, communities did not do enough to prepare for the next time these lines would be redrawn. “Ten years always seems like so far into the future, so we don’t start educating our community members until the next Census count is already happening. By then it’s too late. We need to start now, to prepare our communities for 2030 – and actively track the growth and movements of the Latino community during the next decade. We must do this collectively – no one organization or community can tackle it alone,” Mr. Concepción said. “In the meantime, we need to consistently remind our communities that elections happen every 6 months, not every 4 years, and we need to encourage as much voter registration as possible and make a great effort to turn out the vote.”

For more information about the redistricting process, visit www.redistricting.state.pa.us/commission/article/1087, or contact Miguel Concepción at miguel@concepcionllc.com.